1

Introduction

1.1

Outlining

the Issue

In this paper I will try to show that the development of banknote design

and the use of elements in the design can be seen as a result of a number of

influences: the political and economic foundation of the note, technological

developments, the need to make the notes secure and the possibilities for using

the notes to advocate some cause.

The

specific question under discussion could be phrased as:

“How does the banknote document itself and its contemporary society?”

Paul

D. van Wie (1999, v) states that

The act

of creating coinage is manifestly political. It is also manifestly economic. And there are important, inescapable artistic and

propagandistic overtones as well. For when a political entity creates coinage,

it does not simply create blank disks. Coins generally carry a message: words

and numerals, of course, but usually more than that. Political symbols,

slogans, names, and language, all laden with ideology, bias, self-image, and

national identity.

What holds

for coinage does also hold for banknotes. They are not blanks, but filled with

text, numerals and other symbols, laden with explicit or implicit meaning.

1.2

Limiting

the Scope

The first

Norwegian banknote issue was the third in Europe.[1]

The issue was the notes of Jørgen thor Møhlen in 1695.[2]

This means Danish-Norwegian banknotes gives us more than 300 years of banknote

history and notes to analyse.

I

have virtually no access to actual notes, especially older, but the notes of

the national banks and their predecessors have all been described by Rønning (1980) and Skaare (1995). I have used these descriptions as a basis for my

analysis.[3]

When

I refer to the notes themselves, either individual notes or groups of notes, I

will not refer to any source other than identifying the note(s) or note issues.

A list of note issues is given in Appendix

A, where the relevant references to the catalogues are

indicated.

As a

collector of banknotes for 35 years, I have a lot of knowledge from reading

about banknotes and from studying banknotes, either actual banknotes or

pictures of them. A number of observations, generalizations

and statements will draw upon this knowledge and will therefore not be attributed

to any specific source.

I

have chosen to limit my analysis to the visual parts of the note, i.e. elements

easily visible to the user. Symbols intended to communicate something to the

user will certainly be made easily visible. Other elements, e.g. those only

visible under a magnifying glass, against good light or under ultra-violet light

have been excluded from the discussion, as they primarily are intended to enhance

the security of the issue, not to convey any message.

The

analysis is largely limited to the issues of the national bank and its predecessors.

Private banknotes are excluded, except for the Jørgen thor

Møhlen notes, due to their being the first Danish-Norwegian issue. This

delimitation of official notes is, I believe, in accordance with normal

practice in Norwegian numismatics.

1.3

A

Model of Document Analysis

Niels Windfeld Lund (1999) outlines a model of document analysis. As I

understand him, he sees a document as a result of a

documentation process. His model analyses document production and document

reproduction.

In his analysis of document production,

he sees the documentation processes from three different points of view: The

technical/scientific, the social and the humanist perspectives; and he analyses

five aspects: The producer, the field, the medium, the tradition and the

document.

He also presents a model of document

organisation and a model of document reproduction.

I will limit myself to analysing

those elements of banknote production and reproduction that most affects

banknote design, as this is my focal point in this paper.

2

Analysis

2.1

The

Function of Banknotes

In Lund’s

model (1999, 35) reproduction of a document includes how it is

used. The function of banknotes, as a monetary instrument circulating in

society, is thus a reproduction of banknotes. In his model of document

reproduction, the user and the document takes the place of the producer and the

field in his model of document production.

The

idea or philosophy of money, however, belongs in the analysis of document production,

as the existence of such an idea is a fundamental pre-requisite for any production

of money, in any form.

Money

in the form of coins has a history going back to the 7th century b.c. (Johansen 2001, 89). Coins, until recently, had value due to their

content of precious metals, preferably gold or silver. Coins were produced by

mints controlled by the government, who guaranteed their value in terms of

metal content.

Historically,

banknotes were not money but representations of money, in the sense that they would on demand be exchanged for money, i.e. coins, or that

public offices would accept them on par with money for payments.

Paper

money has no intrinsic value; the value has to be rooted in trust. Trust that

the money I accept will be accepted as payment by others; and trust that the

value will keep over time. If paper money does not achieve trust, it will be

exchanged for coin as soon as possible or used for payment, while coins are

hoarded. In both cases paper money will cease to function as money, it will

loose value compared to coinage or will be redeemed for coin to such an extent

that the issuer will be bankrupt.

In

Denmark-Norway, the first note issues contained text that explicitly or

implicitly (through references to Royal decrees) stated that they should be accepted

as money. Later issues promised that the notes would on demand be exchanged for

silver coin, after the creation of the Scandinavian coin union for gold coin (for

exact wording of promises, see the actual text in Rønning 1980, Skaare 1995). In Denmark this practice

ended in 1962, in Norway in 1945. After this, the notes have been fiduciary

notes, i.e. their value rests upon trust in the issuing authority.

Money,

as seen from a social point of view, has two primary functions that are of

interest: As a medium of exchange and as a store of wealth. This makes it

important that money a) actually can be exchanged for goods or services; and b)

that the value of money is stable over time.

Economic

theory tells us that the supply of money has to expand as the economy grows (see

Glahe 1973, 122–173). This is very difficult to ensure, if the

whole supply of money is based upon precious metals. The issuing of banknotes

was therefore advocated as a means of ensuring an adequate supply of money and

credit. Banknotes also had the advantages of being easier to transport, and

wear and tear did not cause any actual loss of precious metals, as was the case

with coins. Inadequate supplies of silver led Sweden to mint copper as giant

coins (plåtmynt),

weighing up to 19.710 kg (Tonkin 2002, 64) – a paper substitute was welcomed for purely

practical purposes.

Coins

in precious metals also have a strong tendency to be hoarded in times of

unrest, causing problems for commerce and government.

2.2

The

Early Major Design Elements

The early banknotes had major design

elements that today are minor design elements. Below, I will try to describe

their development and to explain why they were important design elements in

earlier times.

One should bear in mind that

the choice of design elements is the producers’ way of inducing the users to

accept paper documents as money; contrary to the

existing ideas of money meaning coined gold and silver, and contrary to the

marked difference in intrinsic value between coins and paper.

Design, as it appears on the

banknote, is a part of the technological perspective of the banknote

production. The reasoning behind design, and the effects of design, belongs to

both the social and humanist perspective of production and reproduction.

2.2.1

Text

All notes within the scope of this

paper contain textual elements. The early notes are very like other official or

legal documents of the 17th century, containing mainly text and signatures

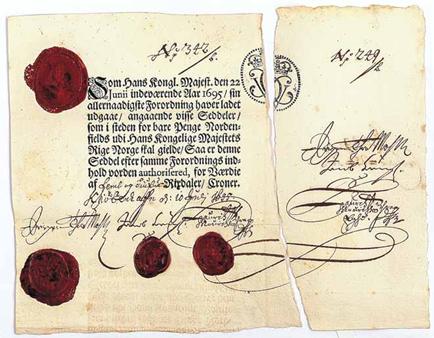

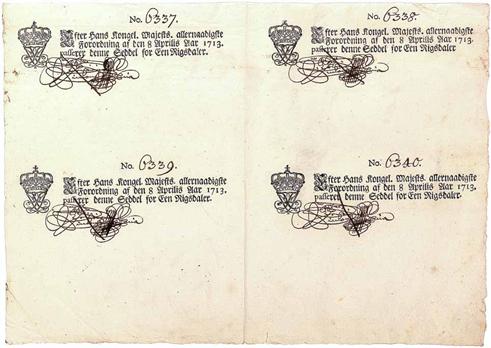

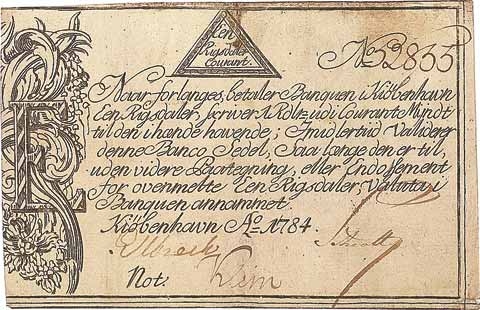

(see Illustration 1 and Illustration 2, p. 25 and Illustration 3, p. 26).

Table 1 clearly shows a trend, starting with long texts on

the 17th and 18th century issues, getting shorter during

the 19th century while post-war notes are virtually without text – the

only texts relevant to the notes’ function being the name of the issuer and the

denomination.

Modern notes are full of

micro-text, as this is a security feature not meant to be read, but to be seen

as lines or other parts of the design (i.e. seen without a magnifying glass), I have not included them in my concept of text in this discussion.

This development is explained below as a natural consequence of the

banknote being a part of; and interacting with, two major document complexes: a

legal document complex surrounding every banknote issue; and a complex of

monetary documents existing at the time the banknote was first issued.

Table 1 Text length of banknote issues[4]

2.2.2

Signatures

All regular Norwegian banknotes are

signed by one or more persons representing the issuer or issuing authorities.

This practise was both a security feature, ensuring that the notes were

authentic; and a guarantee that the promises of the note be held by the issures.

Until 1901, all notes were

signed by hand; from then on signatures have been printed on the notes. As a general rule, signatures, like (and together with)

serial number and year, have been printed in black on the front of the note.

Table 2

Signatures on Norwegian banknotes” shows the development of banknote signatures. The thor Møhlen issue had three signatures on the note itself,

and the same three on the counterfoil. According to the instructions regarding

the signing of the notes, the person signing last should make a scroll on his

signature so that it crossed over from the note to the counterfoil (Rønning 1980, 23).

Later issues had between one

and six signatures, earlier notes tending to have more signatures than later

ones, and high denomination notes having more than low denomination notes. It

is easy to see that the number of notes made signing them hard work, and a

number of persons had this as an occupation. High denomination notes, being

relatively few, could have many signatures, while the much higher number of

small denomination notes did not rate this costly treatment.

From series II (the first

issue with printed signatures) to series III, including the small change notes

and the London issues, notes had only one signature. This was generally the

head cashier of Norges Bank, but the vice chairman of

the board of Norges Bank signed the London issues.

From series IV on, the head

cashier and the head of the central bank (chairman of

the board of directors) have signed the notes together. This return to a larger

number of signatures could be seen as a return to older practices, now without

an extra cost.

In series VII, the signatures

are placed on the back of the notes and they are printed as an integral part of

the design, no longer in a separate printing like the year and serial number.

This would indicate that signatures no longer have a real function, but are

retained as a traditional part of the design only.

Table 2 Signatures on Norwegian banknotes.

Numbers indicate number of note issues.

2.2.3

The

Banknote Legal Document Complex

One of the concepts of Lund’s model

for analysing documents is the document complex (Lund 1999, 34). A document rarely stands on

its own; it is usually one of a number of interconnected documents. One

can often construct a number of such complexes for a given document, depending

on what aspects of the document one wants to look at.

One such complex of documents

that, in my opinion, is important for banknote design is the documents

surrounding the banknote in its early days, making its function possible. It

should be quite self-evident that giving out paper instead of coins in payment

would be met with resistance, and that such an act would have to be preceded by

legislation and information. [5]

The foundation of the thor Møhlen issue lies in a royal decree of June 22nd

1695, in which the King authorises the use of certain notes in parts of Norway.[6] The decree also (among other things) makes use of other types of notes

illegal, and threatens penalties against those refusing to accept the notes as

payment. On July 10th 1695, Rentekammeret[7] issued detailed instruction regarding the design of the notes - how the

signatures should be make, that one third be torn off as a counterfoil, the

placing of the royal portrait, numbering, denominations etc. On August 10th,

information about the notes was sent to various government offices in the area

the notes were intended for, together with an unnumbered note without

denomination, in order that they inform the populace about the notes and how

they were to be used. The project ended with a royal decree

of August 21st 1696 about the recalling of the thor

Møhlen issue.

These documents defined the thor Møhlen issue, with regards to how it should be used and

how it should be designed. It also defined the design in that the whole text of

the note is referring back to the first royal decree as an argument for the

note’s existence and use.

The authorised notes

1713–1728 similarly refers to a complex of documents that the notes are a part of. A royal decree of April 8th 1713 authorises

the issuing of notes, and contains detailed specifications about their design

and use.[8] It also specifies penalties for non-acceptance of such notes. A number

of decrees were issued later, regarding design changes and withdrawal of

certain notes, to be exchanged for new issues. A new decree about punishment

for non-acceptance and regulation of other practises of June 27th

1714 makes it clear that acceptance was not universal. A placard issued by the

chief of police in Copenhagen (in 5000 copies) points in the same direction.

This issue, as the thor

Møhlen issue, has as its major design element a text, pointing at the royal

decree authorising the use of the notes and defining their design, as shown in Illustration 1 p. 25.

Later issues refer to the

bylaws of the issuing bank, or to the duty to redeem notes for silver or gold.

While not explicit, as the documents referred to are rarely directly identified

on the note, this is still references to other documents in the legal document

complex surrounding and including the banknotes.

The change from daler to

kroner is in itself an indirect reference to the Scandinavian currency union

and to the law of currency of April 17th 1875 (Skaare 1995, 1:245) which introduced the new currency and

authorised the issue of certain denominations in coins and banknotes.

Except for the gold

redemption clause on series II notes, 20th century notes have been

free from references to other documents in the legal document complex of the

banknote. There is one notable exception to this. Until the recent issues,

signatures on 20th century notes have been followed by the title of

the signer. On the London issues, however, we find no title but the sentence ifølge særskilt fullmakt, “by special authority”.

2.2.4

The

Precursory Document Complex

Another reason for the textual design of early banknotes

is the fact that the idea of banknotes was not created in a vacuum, but as a

development of an existing complex of monetary document types.

The thor Møhlen

issue was, among other things, meant to replace the practice of issuing notes

(IOUs, obligations) instead of paying out cash to workers at the copper mines

of Røros (Rønning 1980, pp 22-23).

Among the forerunners of the notes of

the Bank of England were the receipts given in exchange for deposits of cash,

and promissory notes (Hewitt and Keyworth 1987, 9-10, 24-25).

The models for the first notes of the

Stockholm Banco (kreditivsedlar)

are a bit unclear, kopparsedlar being

used as an argument but this is debatable (Platbārzdis 1960, 37-38; Lindgren 1968, 11).[9] The later issues of transportsedlar have a likeness with

cheques (Platbārzdis 1960, 78-79), and ran to 4 pages, as they – in principle –

had to be endorsed every time they changed hands (op.cit.,

ill. 81a-d).

This adoption of traditions of

predecessors made the early banknotes typical legal documents, incorporating

text and signatures (and seals) as the major design elements. This is clearly

shown in Illustration 1 p. 25 and Illustration 3 p. 26.

These traditions live on until today in

Great Britain, where banknotes still “promise to pay”, and flourished until

about 1836 in Sweden, when the last multi-page banknotes were issued (Lindgren 1968, ill. 61a-b).

Another predecessor of the banknotes is

coinage. Banknotes were representations of coins, and it is not surprising that

they also inherited some of the traditions of the coinage. Most early banknotes

either had the royal monogram printed on them or embossed on them. The designs

of the embossments, and their circular form, are strikingly similar to the

design of contemporary coinage (for drawings of embossments, see Rønning 1980, 146–148). The printed monograms also bear close resemblance

to monograms on coins. The thor Møhlen issue is a

special case, with the royal portrait (again, similar to a coin) in a lacquer

seal on the notes. This practice of coin-like embossments and royal monograms

continued on Danish-Norwegian and Norwegian notes until – at least – the first

notes of Norges Bank in 1817.

Around 1840 the banknotes seem to be an

accepted fact of life in Norway, and the possibility of exchanging notes for

silver – a long-standing, but un-kept promise – was instated 1842 (Skaare 1978, 57). At the same time, the combination of need to protect

against forgery and development in engraving and printing technology made design

that was more advanced both desirable and possible. From the two-coloured notes

(i.e. notes printed in two colours, a coloured background print and a black

vignette, from 1841) onwards we see a shift in design towards a new tradition,

based in the needs and functions of the banknote itself – freed from the

traditions of legal documents and coinage. Royal monograms have disappeared, so

have embossments. The only break with this is the prominent part of the

monogram of King Haakon 7th on the notes issued in London during the

war (cf. Illustration 5 p. 27).

The representative function still made

text, promising exchange for silver (later gold), necessary;

but now – when the promise could be realized – it was downplayed. This promise

of exchange, making banknotes representatives of “real” money, was retained long

past its reality. It disappeared from Norwegian banknotes with series III in

1945, but the duty to exchange notes for gold had been suspended 1914–1928 and

from 1931 onwards (Skaare 1978, 61). The near absence of text in modern Norwegian

notes reflect their status as fiduciary money, i.e. money which value is rooted

in trust only.

The disappearance of text,

monograms and embossments made space for other design elements. As this

development of banknote design made its start in the 1840’s, this coincided

with the advent of nationalism as a strong movement in Norwegian mental life.

This, as we shall see in part 2.4 “The

Use of Banknotes to Further Ideas of Nationalism” (p. 11), made a deep impression on Norwegian banknote

design.

2.3

Printing

Technology and Design[10]

In theory, a banknote does not need more than a

statement of denomination and, possibly, the name of the issuer, to function as

money. Such a design would, however, be very easy to

forge.

Forged notes have two effects that one

would want to protect against. The producer of genuine

notes would have to redeem more note than was issued; and the trust in the

genuine notes would disappear if forged notes circulated in some quantity.

The history of banknote design can be

seen as a continuing process or battle between actors in a banknote technology

complex: The legitimate banknote producers, i.e. national banks or banknote printing

companies on the one side, and criminals on the other side. This complex can

also be seen as a document complex in which banknotes are a part, as I understand

Lund (1999).

The security elements in banknote design

are chosen so that the note contains a complex of techniques needing

specialised competence and machinery to produce genuine notes, while the costs

of producing notes still have to be kept under control. Another important security

element is quality control, to ensure that all genuine notes have identical

look and feel. If one lets low quality notes out, it will make it easier to

circulate counterfeit notes.

The security features of early notes

were few. They were printed like books, set with loose types. Embossings (i.e.

raised symbols made by pressing a stamp against the paper) that easily became

smudged and incomprehensible when notes circulated, was one security feature.

That the paper was watermarked was probably the best security element. A

weakness in early notes were that denominations were hand-written, not printed.

This made alterations possible. Rønning (1980, 55) shows how this influenced the first notes of Kurantbanken.

Almost 10,000 daler more was redeemed than had been issued,

most of this because denominations had been altered. Only of the

smallest denominations did one redeem forged notes.

Vignettes were introduced to make

forgeries more difficult. One also printed penalty clauses on the notes,

stating that forging them would be punishable by death and that reporting

forgers to the government would lead to monetary reward. This still did not

deter everyone from forging money. Strangely, this inefficiency in preventing

forgeries has not made such warnings disappear. There are

numerous modern banknotes from other countries where such warnings as “La loi punit le contrefacteur”

have their place even today. The copyright symbol on the notes of series

VII may be seen as a modern version of this sign of legal protection.

As printing techniques then meant that

new printing plates had to be made constantly due to wear, one had to keep the

design simple enough that one could make new plates that were identical to the

old ones.

In the early 19th century a

number of techniques were invented, that would transform the design of

banknotes. One was to engrave in soft steel, which then would be hardened. This

made longer print runs possible before engravings had to be worked over or

replaced be new. One also developed the technique of transferring gravures from

hardened steel to soft steel that then was hardened again, so that one could

make a number of identical printing plates, ensuring uniformity and quality of

printed notes. Another invention was a lathe that could make and engrave

complicated geometrical patterns called guilloches,

patterns that it was impossible to make or engrave by hand.

Freed from the constraints of the older

techniques, banknotes now could be filled with colours, ornaments and pictures,

making them pleasing to the eye. This attractiveness must, however, be seen as a result of artistic solutions to the problem of preventing

forgery, not as the primary goal to be attained.

While forgeries had been a major problem

with early issues, the new techniques made counterfeiting a major venture where

a number of competent tradesmen had to be involved, and demanding a large

initial investment.

As new advances in printing technology

made new security features available or made forgeries of circulating notes

easier, the issuing banks issued new series of notes. When photographic

reproduction became a possibility, notes were filled with elements like micro

lettering, making correct reproduction impossible. Today’s colour photocopiers

has necessitated the use of intaglio prints that shows special symbols when

viewed at an angle, metallic holographic elements that cannot be photocopied,

lettering on metallic threads in the paper where the text only can show up

under strong backlight and so on. There are also elements that are only visible

under special light. The watermark is a technique that has survived from the

first days of the banknote. On a modern banknote, everything is filled with

print except – possibly – the area where you find the watermark.

Most modern notes are the result of

three different printing principles: The background is often printed in offset;

major pictorial ornaments are printed in intaglio printing while serial

numbers, years and signatures are printed in letterpress printing. The high

cost of engraving for intaglio printing makes it too costly for printing the

whole note. Engraving, which was a common technique for illustrations, has

almost disappeared from other kinds of documents than paper money, stamps and

other documents where security demands such techniques.

2.4

The

Use of Banknotes to Further Ideas of Nationalism

When text gave way to other design elements,

these elements had other functions than merely furthering the function of the

note, or being neutral decorations. Semiotics tells us that there is no such

thing as a neutral design element.

Semiotics is the science of signs (Fiske1990, 39-60). There are a number of models of the sign,

among them the models of Peirce and of Saussure.[11] What they have in common, is that they see the sign as interplay

between a physical object and a mental image or idea. The physical sign derives

its meaning from the mental sign it evokes in the reader of the sign.

Fiske (1990, 85-92) describes Roland Barthes theory of the two

orders of signification. The first order is the denotation of the sign, i.e.

the everyday, common sense or lexical meaning of the sign. The second order of

signification is described as three ways the sign can work. These are

connotation, myth and symbol. Connotation is the interaction between the sign

and the emotions, values or ideas of the reader, when the reader of the sign

becomes just as important in defining the meaning of the sign as the sign

itself. Myth is an interrelated set of ideas or concepts surrounding some

aspect of life or society. A symbol is an object that through convention has

become a sign of something else. All these aspects of signs are important in seeing

how banknotes in varying degree are expounding nationalism or other ideas.

These ideas also imply that there may be

a difference between the conscious intention of the active user, or maker, of a

sign, and what implications we, as readers of the sign, can draw from it. In

the following, I will describe how I decode the use of signs on banknotes; this

does not necessarily imply intention on the part of the note designers.

Benedict Anderson shows how nations are

constructed as imagined communities. According to Anderson (1991, 170-185), maps and museums are important factors in

this construction. Maps show how the nation is physically delimited and, when

e.g. hung in classrooms, give the pupils a mental picture of their nation.

Likewise, museums show what historical facts and stories are important in defining

the nation. Anderson is writing about emerging nations in what today is termed

the Third World; nations that had been constructed by colonial powers by

drawing lines on a map, regardless of linguistic, economic, religious or

ethnical boundaries or connections. Norway as a geographical term and as a defined

political and national entity goes back to the early Middle

Ages, and is not an artificial construct like many of the nations Anderson

(1991) writes about. Still, Norway has been subservient to Denmark, later Sweden,

for centuries, and has only relatively recently become an

independent nation. The constitution of 1814 made an impact on the

status and political autonomy of Norway; this has been a major influence on the

design of Norwegian banknotes in the 19th and 20th

century.

Maps, as Anderson sees them (ibid.,

170-178), are used to make the geographical definition of the nation stand out

from the rest of the surrounding world, and to define what geographical

entities constitutes the nation; thereby imposing a mental map of the nation on

the spectator. In museums one collects and displays artefacts, thereby

constructing myths, that defines the nation in terms of its history. I will

regard banknotes as a kind of travelling maps or museums, circulating in the

populace and exposing them to the same symbols and myths as maps and museums

do. Banknotes do tell a story, and in the case of Norway, much of the story is

about a nation struggling to define itself in terms of its history.

Another point about banknotes is that

they – at least until modern times – were inherently national. While coins

could circulate well outside the area reigned over by the monarch issuing them

as long as their metal content was as promised, banknotes were backed by

legislation and trust and could not function outside their defined area. Not

until coins lost their intrinsic value, and banknotes could be exported, did

banknotes become an international commodity. The higher denomination banknotes

of Norway (500 and 1000 kroner notes) could not be legally exported until 1982

(e-mail from Bank of Norway, 12.11.02).

2.4.1

The

Norwegian Coat of Arms

The Norwegian coat of arm, a lion standing hold

an axe, is an old symbol for Norway, and was first used on coins about 1285 AD

(Skaare 1995, 1:78). It was also used on coins during the Danish

rule, but was not used on banknotes of the same era.

2.4.2

The

Use of National Symbols before the Kroner Notes

On the notes from the era of Danish rule, we

generally find a royal portrait or monogram in an embossed

stamp or printed on the note. In the days of absolute monarchs, the

state was the area ruled over by the monarch, so using personal symbols of the

monarch would be natural.

With the first notes of Norges Bank came

the use of the Norwegian coat of arms, symbolising the nation of Norway. This

can both be seen as a new tradition, marking the near-independent status of

Norway, and as a natural consequence of the fact that the king was not any

longer an absolute monarch.

Later issues also incorporate symbols of

major industries or trades in Norway; this exhibition of national

characteristics conveys a myth (in Barthes’ sense) about Norway and defines Norway

in terms of its modern economic life.

2.4.3

The

Use of National Symbols on the Kroner Issues

2.4.3.1

Series

I

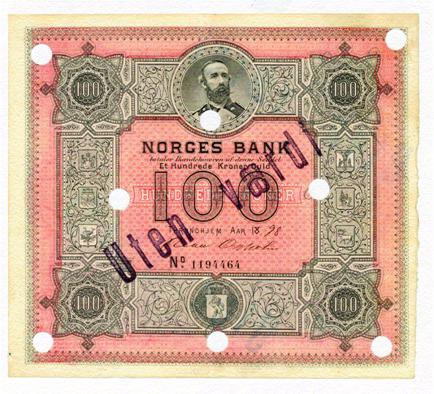

The first series may seem quite

self-contradictory in its use of symbols. A major element is a portrait

of the king, Oscar II, in a Swedish admiral’s uniform (see Illustration 4, p. 26). This is a break with the tradition of having no

royal symbols on the banknotes of Norges Bank. There is no record (Stixrud 1995, 1:39-40) of why this portrait was chosen for the

notes. He is, however, not portrayed as a monarch, he

wears no crown and no title is given, in contrast with contemporary coinage

where his status as king is clearly communicated. And

it must be argued that however much he was king of Sweden, he was also king of

Norway.

Another main symbol on the notes is the

Norwegian coat of arms, a clear indication of Norway as a semi-independent

nation. Yet another set of symbols are the coats of arms of the six bishoprics.

Through them, the note displays how Norway is made up of parts. It should be

noted that these symbols e.g. does not advocate historical claims like claims

to the Norwegian dependencies lost in 1814. To the modern mind, this might seem

quite natural, but both coats of arms and mottos have historically been used to

proclaim dynastic or territorial interests beyond contemporary reality. E.g.,

the title “de

goters och venders” [King of Goths and Wends][12], proclaiming sovereignty over possessions in Germany, was a part of the

title of Swedish kings until 1872, long after the territories in question had

been lost. One should bear in mind that the territorial claims of Norway in

Greenland was not forgotten at the time, Norway occupied parts of Greenland in

the 1930’s and used the historical connection as an argument in the Haag international

court.

2.4.3.2

Series

II

The second series, on the other hand, points in

a nationalist direction only. It was first issued in a period of rising

opposition to Swedish rule, and after an era where national romanticism had had

its heydays. The ornamentation of the notes is clearly marked by references to

ornamentation and symbols from Norway’s Middle Ages. The one person portrayed

on all notes has clear connections to the Norwegian striving for independence

in 1814, while the naval hero depicted on three of the notes was a person

mythologized and romanticised for his derring-do, fighting against the Swedes.

Admittedly, he was serving in the Danish navy, but he was clearly seen as an

example of Norwegian courage and seamanship.

The larger denominations (from 50 kroner

and up) of this issue have historical buildings on the back, together with the

Norwegian coat of arms surrounded by the arms of the bishoprics. Three of the

four buildings are major buildings from the era of Norwegian independence

before Danish rule. Two are castles – one of them built to defend Norway

against the Swedes – and the third is a cathedral devoted to the patron saint

of Norway, worshipped throughout Scandinavia. The fourth building is the mansion

at Eidsvold, where the constitution was worked out in 1814. Seen together, the

notes show us a country looking back to its days of glory to define its

history, showing defiance to its dominating neighbour and union partner. In

their bringing together of defining symbols and conveying the myth of Norway,

they closely resemble the museums described by Anderson (1991, 178-185).

2.4.3.3

The

London Issues

The London issues, with their use of the king’s

monogram as a major design element in addition to the Norwegian coat of arms,

does also break the tradition of not using the king’s person or signs of the

king on the banknotes of Norges Bank. During the war, the king became a very

important symbol for the Norwegians, and he was seen as an important unifying

element at a time when party politics had been discredited. His monogram was a

well-known symbol, and had been used on coins for decades. In preparing for a

situation that could be chaotic, it was natural one should exploit the king’s

standing for an issue of banknotes. It is also telling that in doing so, one

defines Norway as a nation loyal to its king – thereby excluding collaborators

and, possibly, communists who by definition should be anti-monarchists.

2.4.3.4

Series

III

Perhaps the most striking feature of the notes

of series III, if one excludes their almost majestic austerity and lack of

artistic design, is that they actually were chosen for

the monetary reform in competition with the colourful London issue (see Illustration 5, p. 27 and Illustration 6, p. 28). The only nationalistic symbol on these notes is the

Norwegian coat of arms.

The choosing of this issue, instead of

the London issue, may be telling a tale of political considerations. One thing

is the royal monogram on the London issues, possibly excluding the communists.

The communists had become a large political force in Norway and had done great

services in the underground movement, and one should also

remember that the Red Army recently had liberated parts of Northern Norway, at

the cost of many Soviet lives. Choosing the locally designed and produced issue

also paid homage to those who risked their lives to design and produce them,

and hence, in an indirect way, to all those who had been part of the

underground resistance.

The design of these notes also documents

their pre-history. They had to be designed and produced in secrecy, so that

neither the Germans nor the populace got wind of what Norges Bank had planned.

If the Germans discovered what was happening, an ill fate awaited those

responsible. And if the populace found out of the

plans, the whole work would be in vain. Therefore, the notes had to be made

with what little expertise and other resources were available in Norges Bank,

involving as few persons as possible and without access to outside resources

that normally would have participated in both design and engraving.

2.4.3.5

Series

IV

The history of the notes of series IV is long,

starting in 1922 (Stixrud 1995, 1:68) and ending with last notes being issued in

1976 and finally being demonetised and made valueless in 1999. The history of

the design of this issue is told and well illustrated in Stixrud (1995, 1:68-126; 2: ills. 50-71).

Nationalism is still a major part of the

design, no more directed against a common enemy but more trying to instil a

sense of community and common values, telling a myth of a united people

striving together to build the nation. The adverse (portrait side) shows famous

Norwegians (i.e. famous in Norway, internationally neither Michelsen nor Wergeland would be household names). Many of them were also

important in defining Norway or the Norwegian, both to Norwegians and to

foreigners. The reverse shows scenes from Norwegian daily life, with each note

representing a trade or industry: fisheries, trade and shipping, farming,

forestry, mining and industry, and finally arts or intellectual work. In this

way, the notes make a mental picture of Norway and its daily life, with people

struggling together to make a living and to make a community. Monuments and

castles are markedly absent, Norway is no more exhibiting a glorious but

distant history; today’s exhibition is looking forward, at a united country

building the future. An idyllic picture, but one that is

congruent with the post-war political and social climate of co-operation and

inclusion.

2.4.3.6

Series

V and VI

In series V, the nationalism is more downplayed

than in earlier issues. While series II and IV had a discernible nationalistic

programme, the programme of series V seems more to be an exhibition of this and

that that could represent Norway, a kind of tourist brochure telling of famous

Norwegians and nice things to see while in Norway. We have

the same persons as in series IV, less Michelsen, but the reverses are a series

of pictures without any internal connection: fisheries and shipping on the 10

kroner note, Borgund stave church on the 50 kroner note, the Constitutional

assembly at Eidsvold on the 100 kroner note, the University of Oslo on the 500

kroner note and a coastal scene with a lighthouse on the 1000 kroner note.

In series VI, all persons have been

changed. Save for Grieg on the 500 kroner note, we

find persons that were only vaguely known to most Norwegians. The reverses all

shows works of artisans. While the Norwegian coat of

arms is prominently displayed on the notes of series V, it has disappeared in

series VI.

Increasingly, the notes seem to have

lost their function of furthering nationalism and building a nation. The

community building function of creating and displaying a common knowledge of

Norway’s culture is retained, however.

2.4.3.7

Series

VII

Series VII continues the traditions of series V

and VI, in that nationalism as such is no longer a theme, but the display and

communicating of Norwegian culture is continuing.

A new feature in this series is that the

whole note is centred on the person depicted, in that all design elements are

connected to this person. Interesting, too, is the fact that for the first time

a majority of persons depicted may be equally, if not more, well-known

internationally than in Norway.

2.4.3.8

The

Euro

While Norway is not yet a member of the

European Union, the idea of using the Euro as currency in Norway has been advocated.

There is also a possibility that Norway some day will convert to Euro as a

possible future member of the EU.

While Norway’s banknotes have been

nationalistic in their design, the design of the Euro was intentionally

a-nationalistic. No country should find their symbols on the notes; France

should not have a denomination greater or smaller than Germany. Their design is

dominated by architecture on the adverse and bridges on the reverse. No actual

building or bridge is featured; this is “generic” illustrations without any

national overtone. A map of Europe, which – in contrast to the coins – also

includes nations that are not members, the flag of the Union and the stars used

in the flags are the only symbols showing the origins of the notes.

As “circulating museums”, (cf. the first

part of 2.4) these banknotes must constitute problems. How can

they instil a sense of common history and experience in the users, when the

notes shows nothing that can be identified and thereby evoke feelings? The maps

can possibly help make a mental map of the union, but as such, it is incorrect

in that it also shows non-members. The a-nationalistic design of course

overcomes dangers that would be inherent in choosing identifiable objects or

persons to exhibit, but this also curbs the notes in their nation-building

capacities.

2.5

Denomination

The denominations have varied

considerably through the ages. As various issues have been denominated in

different currencies – all named daler,

but with differing actual values in silver coin – I will not compare the

denominations of the different issues.

Until about 1750,

denominations generally were handwritten in the text of the note, and numerals

were not used until about 1750. From then on, the denomination was printed in

text and numerals. This has implications regarding the users of banknotes. In a

country where most of the population were analphabets,

textual documents could only function well in the classes who could read and

write, i.e. the middle and upper classes. The choice of denominations also

indicates that these classes were the intended users. Later developments,

necessitating increasingly lower denominations, also brought forth numerical

indications of denomination, making it easier for analphabets

to use banknotes.

Denominations varied with the

state of the government finances. In hard times, banknotes were issued for

small amounts, in better times only notes denominated with a value of at least 1 daler were issued.

The kroner notes were first

issued as 5, 10, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 kroner notes. This series of

denominations has been surprisingly stable; the 5 and 10 kroner notes were

abolished in 1963 and 1984 respectively, while the 200 kroner note was introduced

in 1994.[13]

This stability is not matched

by a corresponding stability in the value of the kroner. The purchasing power

has dwindled to a mere 2 per cent of the original value since the kroner were

introduced in 1875. This means that the 5 kroner note had a purchasing power of

about 250 kroner today. At the same time, the real value of wages, or the

purchasing power of labour, has increased strongly. 5 kroner represented two

and a half day’s labour for a skilled labourer of 1875 (Statistics Norway. n.d.). The 1000 kroner note represented a purchasing power

of 50 000 kroner today, and was equal to about two years’ pay in 1875.

The mismatch between the

development of the denominations of notes and the purchasing power of the

kroner will be further discussed in the following.

2.6

The

Competition with Other Forms of Money

There are numerous types of money,

banknotes are just one of them, and a type we know well from our own

experience. In reality there are, and have been, a number of document complexes

competing for the role of money in society.

2.6.1

Coinage

At the start of the era of

banknotes, gold and silver (and to some extent copper) minted as standard coins

with a denomination close to their intrinsic worth, were the only universally

accepted money in Denmark-Norway.

As discussed in part 2.1 “The

Function of Banknotes” this kind of money had some weaknesses that

banknotes could overcome. However, banknotes were obviously seen as a poor

substitute for real money by the populace. The number of royal decrees

threatening punishment for non-acceptance and otherwise enforcing the use of

banknotes shows this.

Gresham’s law (cited in Scott 1930, 26) says that poor money will drive good money out

of circulation. This means – in our context – that given the choice between paying

out gold or silver coin on the one hand, and banknotes on the other hand, you

will always give away the banknotes (as long as you perceive them to be

inferior in value) and keep the coins. The effect of introducing banknotes will

be that coins disappear from circulation – not because banknotes are seen as

better, but because they are deemed inferior.

Banknotes were normally

issued as notes that could be exchanged for gold or silver coin on demand.

Normally, legislation would put limits on the total outstanding issue, either

as an absolute sum or as a sum or factor over the issuing bank’s actual holding

of gold or silver.

If too many banknotes were

issued, holders would come to the bank and demand coins in return. If enough

did this, the bank could not meet its obligations and redemption would have to

be suspended – reducing the credibility of the bank and its issues even

further. The issuers thus had ample reason to strive for parity between their

notes and coinage.

While these mechanisms

holding the note issues within limits obviously had their function protecting

the economy against strong inflation, they also had their drawbacks. This was

fully demonstrated in Norway during the 1920’s and 1930’s, when Norges Bank

followed a monetary policy aiming at restoring redemption of notes for gold at

the rate stipulated in 1875. This policy led to deflation and an economic

crisis, which took years to overcome. Norwegian notes have been irredeemable,

fiduciary notes since 1931 (despite their own wording until 1945) and this has

been efficient. In reality, the competition between gold and silver coins on

the one hand, and banknotes on the other hand, was over when Norway stopped

minting silver circulation coins in 1920. For all practical purposes, coins

without actual intrinsic value cannot compete with banknotes – at least not for

payment of larger sums.

2.6.2

Documentary

Payment Forms and Bank Accounts

As shown in 2.2.4 “The

Precursory Document Complex”, banknotes had other documents as predecessors.

These documents – drafts, bills of exchange, obligations, cheques etc. – lived

on, parallel to banknotes. They had proved useful in effecting transactions

between merchants, and have lived on until this day. They were, though, not

general instruments of payment, so they could only partially compete with banknotes.

With the advent of a

well-functioning banking system, some of these instruments – like the cheque –

gained strength. New monetary instruments, directly competing with banknotes

and coinage, also saw the light of day. The most important such instrument was

the bank (or savings) account.

Hoarding money, be it coin or

banknotes, had been the only way of storing monetary wealth. In a society where

there were few institutions of credit, you had to save money to invest in e.g.

a farm, a house or a fishing boat. Hiding away cash was one of the important

ways of saving. (A more productive way was to buy a part of a farm.) When the

first savings banks were started, one of the reasons was to give savers a safe

place to put their money, safe from fire and theft – and even accruing

interest. Gradually, such accounts came to take a major place as a store of

wealth, in direct competition with coins and banknotes.

A further development came

with the increasingly more effective services of account-to-account transfers.

This made it possible to settle debts over long distances and without actually

involving cash. Folio accounts increasingly took over many monetary functions.

With the introduction of

electronic data processing for keeping accounts in the Norwegian banking system,

one had the resources to process a large amount of cheques. In the 1960’ and

1970’s the old practice of paying out salaries in cash gave way to transfers

from the bank accounts of employers to the checking accounts of employees, and

checks became the preferred method of payment for medium sized and large

amounts.

2.6.3

Plastic

Money

A development of bank accounts are

“plastic money” or “electronic money”, money substitutes (competitors) based on

a bank account (or a similar device).

“Plastic money” got its name from the plastic cards associated with them.

These stem both from the credit cards that were invented in the US in the

1950’s, and from the check guarantee card used by Norwegian banks to facilitate

use of checks in the 1960’s and 1970’s. These cards were developed into cards

that could be used to get cash from an ATM (Automated Teller Machine or Cash

Dispenser), later to pay at an EFTPOS terminal[14] in a shop.

These instruments were

developed to take the place of checks, that had proven very costly, and to

minimize the need for cash handling in shops and banks. The effect is that with

a small card you can have full control of you bank account, without ever visiting

your bank and with the use of very small amounts of cash.

“Electronic money” are

solutions that makes it possible for you to effect payments and other

transactions electronically, e.g. through your bank’s internet banking solution.

For the banks, the point is

that as long as they can make you keep your money in your account, it can be

lent to others. At the same time, they want to avoid the costly and risky

handling of cash amounts, and they transfer the manual work with money transfer

from themselves to their customers.

Cash, both as coins and as

banknotes, have been relegated to a secondary place in a modern society’s

payment and wealth storing systems.

2.6.4

The

Unofficial Economy

While the amount of actual cash in

circulation has had a slow decline over the last 10 years, measured as a

percentage of GDP or household income, the last two years has seen a decline in

the actual amount circulating. It is still an astonishing 40 billion kroner or

about 8000 kroner per capita (Norges Bank 2002, 33-34). Most of us will reflect that this amount is

very much larger than we usually have lying around.

Anyone with a practical

banking experience will know that a number of people, especially elderly, have

deep-rooted suspicions against banks and will prefer to hoard their wealth in

the form of cash.[15] This often comes to light when they are robbed, or when unsuspecting

heirs come across large amounts when tidying up – or upholstering old

furniture, redecorating rooms or otherwise.

Another class of customer are

those who fear taxes more than death, preferring to keep cash in bank vaults

instead of in interest bearing accounts.

The major explanation of the

large amounts of cash in circulation is probably crime. Not the petty wealth

tax avoidance described over, but large-scale tax avoidance

and smuggling and distribution of heavily taxed or illegal substances –

alcohol, drugs, and narcotics (Norges Bank 2002, 33).

In order to make the

transport and hiding of large sums impracticable, Norges Bank does not want to

make notes of larger denominations than 1000 kroner. As shown in 2.5 “Denomination” the decline in value of the kroner since 1875 would

have made making larger notes reasonable, but the growth of other means of

payment for legitimate trade makes banknotes a means of payment for minor sums

outside the black-market economy. Other countries have abolished their larger

denominations, e.g. Sweden the 10,000 kroner note, USA the notes of 10,000,

5,000, 1,000 and 500 dollars, UK notes over 50 pounds etc. It is also a point

that the fight against white-washing makes it a goal

to make most transactions traceable, which they will be when handled as account-to-account

transfers or by other electronic means of payment. In this respect, banknotes

have become impractical documents for the authorities.[16]

2.6.5

Overall

Picture

Banknotes won the competition

against coinage to become a preferred means of payment during the first half of

the 20th century. In the same period, banknotes have been fighting a

losing battle against other forms of money for storing wealth.

Developments in banking, made

possible by extended use of information technology, has over the last few decades

brought forth new forms of money, leaving little room for banknotes in the

legitimate economy.

The fight against the

black-market economy has also curbed what would have been a natural development

of the banknote institution.

3

Conclusion

Tradition is

one of the aspects in Lund’s model for document production (1999, 30). But can we talk of a

tradition of banknote design? The techniques used for production have changed

over years, the role of banknotes and their function has changed, and so has

their appearance. The monetary ideas behind banknotes have also changed.

I

believe it is wrong to demand total stability from a tradition. Yes, banknote

design has changed markedly in the 300 years they have been with us, but so has

their times. The hallmark of a tradition must be that things change in response

to changed circumstances, in order to preserve the functioning of the central

theme of the tradition – in this case the banknotes. Traditions that are not

adaptive will cease to exist. So far, banknotes have shown a remarkable degree

of adaptation to changed circumstances.

I

will conclude that there is a tradition of banknote design, and that this

tradition has changed as external influences have made it necessary. Major

external influences have been introductory problems with acceptance,

inflationary practices, forgery, printing technology, ideological changes,

economical changes, the unofficial economy and changes in the concept of money.

Given

the development of banknotes as presented in this paper, one could pose the

question: “Is there a future for banknotes?”

Banknotes

have gone from representatives of real money to everyday and trivial instruments

of payment. Their design has become increasingly complex in order for them to

be trusted. They have met serious competition from other monetary instruments. Technological

change, not in the design and production of banknotes but in the making of

other kinds of money, e.g. electronic money, will be the major obstacle for

banknotes. Norway probably will develop technologies that will make banknotes

superfluous for most of today’s users. Tourists, who will have difficulties in

integrating themselves with an electronic monetary infrastructure, will

probably be the last legitimate users of banknotes. The unofficial economy will

still need cash; this is one of the major reasons for abolishing banknotes.

Given the historical development shown in the preceding, one could

prognosticate that Norway should abolish banknotes sometime between 2010 and

2020.

Money

will then be electronic and traceable, and will be transported or controlled by

plastic cards like those we know today. They are designed as billboards,

marketing national and international private financial institutions. They, like

the Euro, will lose the function of “travelling museum” and will not create

communities like those that today’s banknotes do. This will be a loss in our

everyday life.